[ad_1]

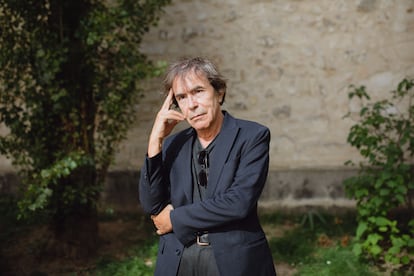

The philosopher François Jullien (Embrun, France, 1951), a specialist in Greek and Chinese thought, holds the chair of alterity at the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme Foundation in Paris, where he receives us in an immense glass-enclosed hall that seems Straight out of a Jacques Tati movie. Just published Truly alive. Small treatise for an authentic life (Siruela), where he questions a common fear in these times: that of living an existence devoid of content, buried by routine, alienated by the forces of the market and technology, and turned into a simulacrum or, even worse, into a vulgar parody.

Ask. In the book he says that this suspicion is “perhaps the oldest in the world.” Where does the obsession to live a full life come from in the face of a supposed second-rate existence?

Answer. I don’t know if I would speak of obsession, which seems a bit harsh to me, but it is a subject that appears very early in the history of thought. Plato already talks about it, although for him authentic life is the afterlife, what comes after death. Rimbaud, Proust and Adorno also mention the subject, but do not dwell on it much. I wanted to turn it into a tool for existential and political reflection.

If you want to support the development of quality journalism, subscribe.

subscribe

Q. He wrote the book just before the lockdown. Has the pandemic intensified our aspiration for that full life?

R. The pandemic has led to the confusion of life and vitality, the living and the vital. For me, only the first counts. I have wanted to move away from both Platonism and the exuberant vitalism of Nietzsche. Life is not just vitalism, it goes much further.

Q. How have the last two and a half years changed us?

R. We are witnessing an imposition of virtuality, of permanent connection, when what should be done is to reawaken the power of life without withdrawing it into the digital. Loss and absence are very important: they intensify authentic life even more, they make it emerge. The comfort of the virtual seems dangerous to me.

“Self-help seems deplorable to me, because it is in no way equivalent to thought. It is a sticking plaster, a band-aid”

Q. With the successive crises and the war in Europe, many of us had the feeling of finding ourselves inside a fiction. He writes that this feeling of simulacrum is not new.

R. That’s how it is. The risk is that this leads to disenchantment, generalized disappointment, when what we have to do now is to work on our lives, to reform them. In Europe, philosophy has avoided talking about how to live because it didn’t have the tools to do it. Traditionally that question had been left to religion. With the receding of the religious in our societies, who is assuming that role? Self help.

Q. In the book he is very critical of the so-called personal development, which he calls pseudo-philosophy. Are their authors charlatans?

R. Yes. They have created a happiness market, a unique thought that sells us false wisdom about life. I find it deplorable, what they do is in no way equivalent to thought. They are Neo-Stoics or Neo-Epicureans, at best, but without the rigor that the Greeks had. For me, thought must resist the market, trade. Self-help is little more than a tape, a Band-Aid.

Q. He uses Marxist terms such as alienation or reification. Why are they relevant to describing the world today?

R. I am in favor of updating them, they describe well the tendency to withdraw that I describe and the need to resist it. The difference with the 19th century is that then alienation had a face. Now it no longer has it: it is everywhere, linked to the ubiquity of the globalized market and the incessant connection. It is not a question of criticizing technology, but of understanding what new forms of alienation it has provoked and to what extent it is more difficult to combat them than in Marx’s time, because alienation no longer has the appearance of the bourgeois owner.

“Living is a contradictory experience, which takes place in the chiaroscuro of passions, in the confusion of feelings”

Q. Is there a good way to live and a bad way?

R. That’s what the Greeks believed, but luckily we’ve already outgrown their happiness ethic. It is better to get away from that permanent dramatization. I do not believe in happiness or misfortune. Don’t ask me if I’m happy, it seems like a meaningless question to me. Nor do I believe in the goals that many set for themselves to give meaning to their lives. I believe, rather, in having resources, in having a series of tools so that life becomes more intense.

Q. In this regard, he defends the usefulness of emotions, which have not been of great interest to philosophy either, having considered them “a sudden outpouring that dethrones the autonomy of the subject.”

R. Emotion supposes a set in motion, the emergence of an intensity that seems positive to me. We must accept that living is a contradictory experience, which takes place in the chiaroscuro of passions and the confusion of feelings. Among other things, I miss emotions in politics…

“I preferred the Italians singing opera on the balconies than the French applauding the doctors. It seemed like simulated emotion to me.”

Q. Really? Aren’t there too many already?

R. There is a lot of irrationality in political discourse, but not an emotion that mobilizes and stimulates you. It is a sensitive issue, because emotions can lead to destructive manipulation, as happens in dictatorships. But I believe that there is also a fertile political emotion, like the one that arose in the first days of the French Revolution, a collective feeling that puts our lives in tension again. The disaffection for the policy that we observe today prevents a set in motion, a new takeoff.

Q. Don’t you think that the pandemic has been a political cycle very marked by emotions?

R. The pandemic could have sparked that mobilization, but it did not. At least in France, where politicians limited themselves to giving subsidies. He preferred the Italians singing opera on the balconies than the French applauding the doctors. I thought it was a simulated emotion. And that can be nice and even interesting, but in no case is it political; it is not a mobilizing emotion that reactivates the political. We missed that opportunity and I’m disappointed.

Q. He is a strong defender of European cultural identity. Do you think it will survive the latest crises?

R. The question of our cultural identity is never discussed in Brussels or in Strasbourg, when it is essential. Europe needs a second life. You must defend your freedom and your diversity. Their languages, for example. I am a great militant of European languages against Globish (English spoken by non-natives to understand each other). You have to bet on French, on Spanish, on Catalan. And not because of chauvinism, but because they are cultural languages that give us resources for understanding. I am fully convinced that the world still needs Europe.

sign up here to the weekly newsletter of Ideas.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

[ad_2]