[ad_1]

When Margareta Magnusson (Gothenburg, Sweden, 89 years old) began to empty her father’s house after his death, she found at the bottom of a desk drawer in the office where she had worked as a doctor throughout a whole life a huge package. It was a block of arsenic. “I suppose that, in times of war, it was something that people had at home in case of need,” Magnusson explains, from Stockholm and by video call, to EL PAÍS. The block of arsenic had been in that drawer since World War II, when the family feared the Nazi invasion. And she stayed there for more than 30 years. Magnusson wasn’t quite sure what to make of it. The arsenic, unfortunately, did not come with an informative label indicating which container it should be thrown into. Finally, she decided to take it to her trusted pharmacist who, although he was somewhat perplexed to see that block of poison, took care of it.

“My mother, on the other hand, was a very orderly, wise and realistic woman,” explains Magnusson. She spent a long time sick before she died. When Magnusson began emptying her house after her departure, he found a series of notes pinned between her clothing and her belongings indicating what she was to do with it all. There were some packages ready to donate to charity, some books to be returned to their owners or an old suit to take to the History Museum, with a note pinned to the lapel, which even included the name of the person to whom it was due. should contact. “That was a relief and, in a way, I felt as if my mother was still there with me, guiding and helping me through the whole process,” he recounts. On that occasion, emptying the home of her possessions and memories was a much easier process for him and, fortunately, he did not require any visits to his pharmacist.

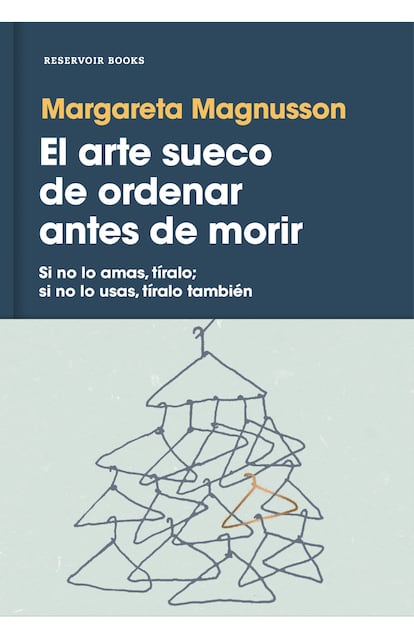

It was his mother who inspired Magnusson to write his essay The Swedish art of tidying up before you die (Reservoir Books, 2017). In Swedish it is called dostädning; do means death and standing, cleanliness or order: “It is a term that refers to getting rid of everything unnecessary and turning our home into an orderly and welcoming space when we believe that the time to leave this world is approaching,” explains the author. As she relates in the book, the term itself is quite recent, but the dostädning It has been practiced for years: “I think that women have always practiced it, but their work is not usually put under the spotlight and should be more valued. In my generation and before, women tend to clean up when their husbands pass away and then again before they leave themselves.”

He dostadning It has nothing to do with other organization techniques that have become so fashionable in recent years, such as those of the Japanese Marie Kondo and her well-known KonMari method. “I have read her book and it was an interesting read, but my approach is completely different: Marie Kondo is committed to organizing spaces and keeping everything tidy, with the idea of having more space available for more things. I bet on throwing it all away, ”explains Magnusson.

“Taking inventory of all our old belongings, while remembering the last time we used them and, if possible, saying goodbye to some, is not an easy task for many of us. People tend more to accumulate things than to throw them away, ”writes Magnusson in his book. And he reiterates it in the conversation: we have too many useless things in the chests of drawers and on the sideboards, we keep too many possible wardrobe items in our closets, we have kitchen cabinets full of gadgets that we haven’t used for years, because we may always end up cooking with the same pot, the same frying pan and the same wooden spoon, and we have a bathroom infested with products, some of them expired, others already useless and others (nail scissors, tweezers) often duplicated and even tripled. “I have had to order so many times after another person died, that I would not even come close to forcing someone to do it after my death,” explains the writer.

Cleaning up death may seem like a pharaonic work to many. The truth is that it is. As Magnusson details, it is not a normal cleaning or a simple change of cabinets and the process can take months. No hurry. What there are are certain tricks: “Start by checking the basement or the attic or the hall closets. These areas are perfect for starting to get rid of excess stuff.” Perhaps, many of the things stored have been there for decades, we may not even remember that they existed: that is the right signal to get rid of them. Afterwards, you can move on to the storage areas (that old ski equipment, the old dolls, the Carnival costumes). “I no longer have anything in the attic or basement,” Magnusson says proudly, “but that doesn’t mean I don’t have things: I have paintings that I love and some furniture that I find pretty or have a story with.” The difference is that he already knows what will happen to them after his death: either some of his children will keep them or they will be donated.

The writer also recommends pulling in friends and family. Perhaps a nephew, a grandson or the son of a friend has just moved into a first home and that closet or chest that takes up so much space and that will cost so much to get rid of later on can come in handy. Or maybe that book-guzzling friend is delighted to pick up that almost-forgotten crime novel series. Magnusson proposes to stop buying things and give those belongings that we already have and that have a certain sentimental value to our loved ones (vases, potted plants or decorative objects, for example).

The last thing should always be memories: “For starters, reviewing our photographs makes us very sentimental. There are many memories, memories that we want to keep, perhaps pass on to our family”, writes Magnusson. The author advises that when the time comes to order and throw away the photos of a lifetime, once the copies and negatives that are already useless and accumulated in any way have been discarded, it is best to meet with family and friends: “This way, you become the task into something less lonely, less overwhelming, and more fun—plus, you won’t have to carry the weight of all the memories by yourself, and you’re less likely to get stuck in the past.”

There are memories and memories. Some that we want to share with family, others that we don’t. Like all those old love letters, those old tapes from a road trip, that movie ticket from a first date, or those plane tickets from a special trip. What for anyone else may be just junk, but for oneself is the memory of a lifetime. Magnusson, contrary to what he may seem, is not against sentimentality, but he is a practical person. The solution to all this is a box to put everything. Keep it close, revisit it as many times as you want, but don’t forget to leave a message: private, to throw away.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

[ad_2]