[ad_1]

When she was a child, in Buenos Aires in the eighties, Sofía Achaval liked to dress up and put on makeup, invent characters. Her older sister collected copies of Vogue and she also looked at the Argentine magazine Para Ti. “She knew the names of all the models and designers,” she smiles. She spent entire afternoons at her great-aunt’s house. French and childless, she was a woman with a special sensitivity for colors and decoration. “Everything was light blue, blue, velvet,” describes Achaval. “She had incredible clothes: some coats, some bijous, some make-ups.” The great-aunt lived in a Haussmannian porteño building, typical Parisian urbanism of the 19th century. “It was like being in Paris,” she says.

Another object of fascination, at the same time, were the gauchos: the men from the countryside who dressed in felt hats, panties, decorated belts called harrows. I would see them on weekends and vacations at the family property in La Pampa. “Since she was a girl, she thought: ‘What elegance! What style! ”, she recalls.

At the age of 22, he landed in Paris to study fashion at the prestigious Studio Berçot. Then two unexpected things happened to her. The first was that nothing seemed exotic to him in Paris. She felt at home. The streets, the houses, even the rituals of the gentry and the high intelligentsia: nothing was new to her. Saint-Germain-des-Prés was not that far from La Recoleta. The second unexpected thing was that when she was walking around dressed in the gaucho style, the young Parisians would stop her and say: “I want these pants, this poncho, this bloomer”.

The outcome was inevitable. When, in 2018, and after working for others in the world of haute couture and fashion magazines, Sofía Achaval created the Àcheval brand together with Lucila Sperber, what emerged was a compendium of all this history and this geography. Àcheval is a play on words with Sofía’s last name and the phrase that in French means “on horseback”. The brand summons childhood experiences and dreams of crossing the pond. It is the spirit of the gauchos —they manufacture in Uruguay— in rare alchemy with the fashion elite: Milan, home of the Àcheval showroom where the collections are presented; and Paris, the co-founder’s base camp. “For me the gaucho style was always an inspiration,” she says. “With Lucila, we had the idea that we had to do something with this, so strong and so ours. The world wants it. We transform it in a contemporary way.”

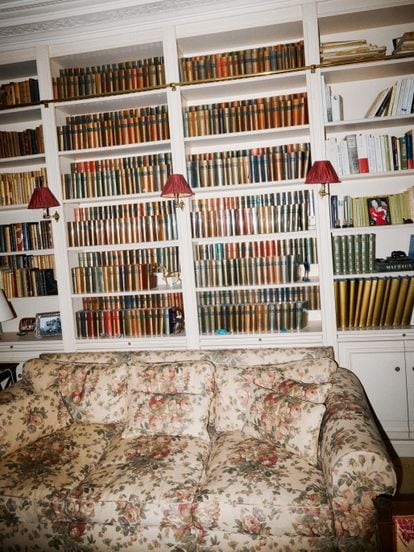

Sofía Achaval tells it on a sofa in the apartment on the rive gauche in Paris where she lives with her husband, the writer Thibault de Montaigu, and their children, Tadzio and Paloma. Vogue has described her as “a Botticellian figure with wheat-colored hair.” Today the “botticellian” is mixed with the “maradonian”: the day we visit her, she is wearing a Boca Juniors shirt, brand Àcheval, with the number 10 of Diego Armando Maradona. “Maradona fan!” she proclaims herself. We walk through the house: the shelves with the collections of La Pléiade de Gallimard, the publishing house founded by Thibault’s maternal great-grandfather. The photos of the wedding in Uruguay, she dressed as Christian Lacroix (they had previously married civilly in Saint-Tropez). The bright window that overlooks the chestnut tree of the interior patio.

Jacques Lacan, the priest of psychoanalysis, had his practice in another apartment in the same building. In the corridor hung The Origin of the World, the famous painting in which Gustave Courbet portrayed the close-up of a woman’s sex. It is now on display at the Musée d’Orsay, four steps from here. On the street a plaque indicates: “Lacan practiced psychoanalysis here from 1941 until his death.”

“The Argentines stand in front and try to get in,” says Achaval. Because this is also a history of psychoanalysis: Argentine and French. Thibault’s latest novel, Grace, is autobiographical and tells of a conversion to Christianity. It all begins with a visit by the narrator to a psychoanalyst while she lives with her family in Buenos Aires. “I also analyze myself,” Sofía confesses. “I had not analyzed myself much in my life, only as a teenager. And now, as a grown up, I wanted to, but more than anything as a curiosity and a personal investigation. Like an internal journey”.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

[ad_2]